Have you ever stood in a fast-food line, paralyzed by choice?

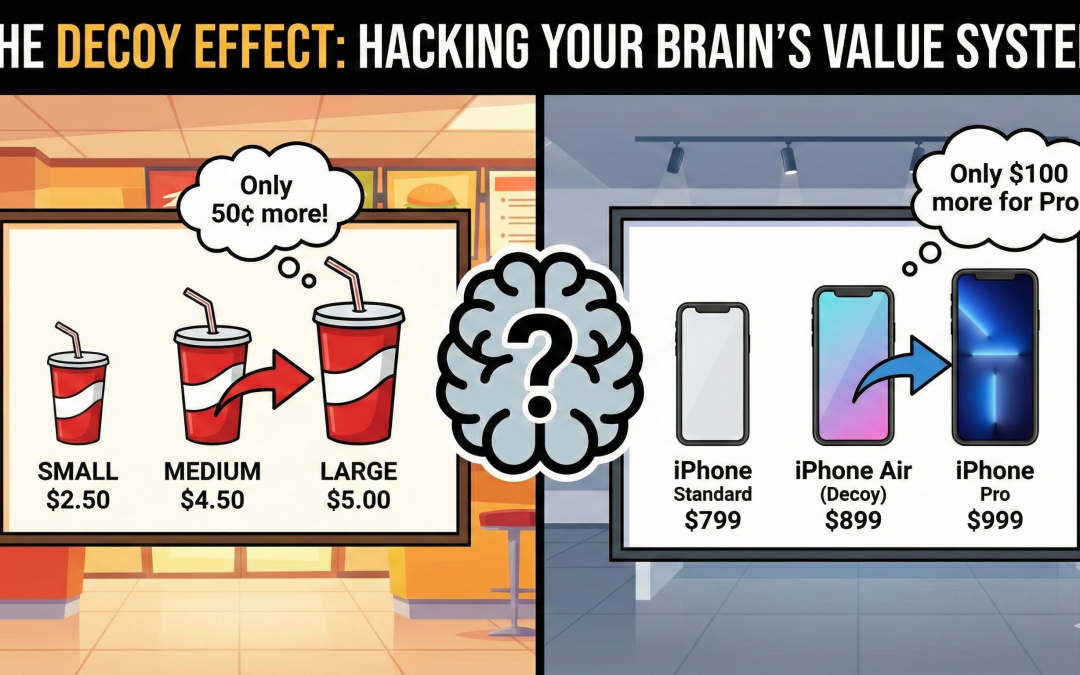

You’re looking at the soda options. The “Small” is $$$2.50. The “Large” is a massive bucket of sugar for $$$5.00. You think, “I don’t need that much soda, I’ll take the small.”

But wait. You notice a third option: The “Medium” for $$$4.50.

Suddenly, your brain does a quick calculation. “Wait a minute. For just 50 cents more than the medium, I can get the huge one? The large is a steal!”

You walk out with the $$$5 giant soda you didn’t originally want.

You just got hit by the Decoy Effect. And while it works for selling fizzy drinks, it works even better for selling $$$1,000 smartphones.

What is the Decoy Effect?

In behavioral economics, the Decoy Effect (also known as the “asymmetric dominance effect”) is a phenomenon where consumers change their preference between two options when a third, less attractive option is presented.

This third option—the “decoy”—isn’t really there to be bought. It’s there to mess with your perception of value.

We humans are terrible at judging absolute value. Is a phone worth $$$999? I don’t know. But we are excellent at judging relative value. Is Phone A a better deal than Phone B? We can figure that out instantly.

The job of the decoy is to be the “ugly sibling” that makes the product the company actually wants to sell look incredibly attractive by comparison.

A Hypothetical Case Study: The Apple iPhone 17 “Air”

Apple is brilliant at simplifying choices while simultaneously nudging you up the pricing ladder. They’ve done it for years with storage tiers.

Let’s run a thought experiment for a future launch: The iPhone 17 lineup.

Imagine Apple wants to drive massive sales of their high-margin iPhone 17 Pro. How do they guarantee people don’t just settle for the standard, cheaper model?

They introduce a decoy. Let’s call it the iPhone 17 Air.

Here is the hypothetical lineup presented to you on stage:

The Setup

- iPhone 17 Standard ($$$799): The reliable base model. Two cameras, standard aluminum body, great chip (A18). A solid phone for most people.

- iPhone 17 Pro ($$$999): The target product. Titanium body, three pro-level cameras, 120Hz smooth display, the fastest chip ever (A19 Pro).

If these were the only two options, many consumers would look at the $$$200 difference and say, “Eh, the standard is fine for me. I’ll save the money.” Apple loses out on that sweet Pro margin.

Enter the Decoy

Apple introduces a third option right in the middle to disrupt your thinking.

- iPhone 17 Air ($$$899): It’s incredibly thin and light—that’s its only selling point. However, to make it thin, it has smaller battery life than the Standard, only two cameras, and the standard 60Hz screen.

Now, look at the lineup again through the lens of a consumer:

- Standard ($$$799) vs. Air ($$$899): Why would I pay $$$100 more for the “Air” just because it’s thin, when it has worse battery life? The Air looks like a bad deal here.

- Air ($$$899) vs. Pro ($$$999): Now your brain starts buzzing. You look at the “Air” for $$$899. Then you look at the “Pro.” You realize that for only $$$100 more than the overpriced Air, you get the Titanium body, the third camera, the incredibly fast screen, and the best chip.

Suddenly, the $$$999 Pro doesn’t feel expensive. It feels like the smartest financial decision on the board. The “Air” makes the “Pro” look like a bargain.

In this scenario, the iPhone 17 Air is the decoy. Apple doesn’t care if they sell a single unit of the Air. Its entire purpose is to exist on a pricing table to push fence-sitters toward the Pro model.

Why Our Brains Fall for It

The Decoy Effect works because it relieves cognitive strain.

Making decisions is hard work for our brains. When faced with Option A (cheap but basic) vs. Option B (expensive but premium), we get stressed trying to weigh the pros and cons.

The decoy offers an easy way out. It provides an obvious comparison. The decoy is clearly inferior to the target product (the Pro), but priced similarly. It allows our brain to make an easy “A vs B” comparison and ignore the rest.

We say to ourselves, “Well, only an idiot would buy the Air when the Pro is right there for hardly any extra money.” We feel smart for dodging the bad deal, and in doing so, we fall right into the trap of buying the expensive one.

The Takeaway

The next time you are looking at pricing tiers—whether it’s for software subscriptions, cars, or coffee—look for the decoy.

Look for the “medium” option that offers very little extra value over the “small,” but is priced suspiciously close to the “large.”

If you can spot the ugly option, you can step back and ask yourself: “Would I still buy the expensive one if this middle option didn’t exist?”

If the answer is no, you’ve just spotted the decoy effect in action.

“Mastering the psychology of price is the fastest way to increase your margins without spending a dollar more on manufacturing. If you want to learn how to architect your own pricing tiers and participate in a professional pricing session, book a course on Bizmaze today.“